How long have advertisements affected your idea about women? Bournemouth’s department stores in the 20th century.

In December of 2018, the ASA (Advertising Standards Authority) announced a ban on advertisements that included gender stereotypes that could cause harm or widespread offense. The new rule does not affect adverts that portray men and women doing the regular stereotypical tasks, but it does mean that ads cannot show someone failing to do something because of their gender. Seeing all the news coverage about the myriad of adverts being taken down because of this rule made me think, how long has this been going on? How long have companies used gendered advertisements to propel their profits while simultaneously pressuring and reinforcing society to function based on those stereotypes.

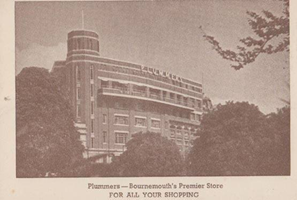

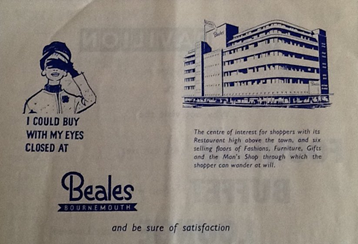

Department stores had been the backbone of communities in the 20th century, and Bournemouth was no different, stores like Plummers & Roddis, Bobby’s and Beales were central to Bournemouth’s high street. They advertised in local newspapers and magazines, and with posters on public transport and in mail leaflets. Press and newspaper was considerably more accessible for smaller stores and guaranteed a wider reach, but the posters and mail leaflets allowed stores to target audiences more specifically. Still, all types of ads had a significant role in perpetuating ideas about women in fashion and shopping to boost their sales. That being the case, looking at the ads and their influence shows us how women were portrayed nearly 100 years ago, so this has been going on for women for all that time. One example of this in Bournemouth is some of the ads from Plummers & Roddis.

The ad above is a gift guide promoting the stock they sell, what is unseen here is that it appears in the “for Women” section of the Bournemouth Weekly Graphic in 1936. It is placed conveniently under an article discussing women’s fashion of the time and makeup tips. While the ad itself may not present any clear expectations of women, the positioning of it following the “tips and tricks” in fashion for women suggests that the shopping experience and purpose of department stores was for women to be the main consumers. Especially in the post war eras (1930s & 1950s) the consumer, who shopped to prepare and equip a household, was traditionally defined as female. Women were encouraged to be housewives in order to get women out of the workplace they had entered in wartime, to make room for men re-enter. Due to this, women would shop for the family, and have time to shop for fun. Therefore, even early in the 20th century stereotypical ideas of women and their primary roles in society as housewives were enforced to women through advertising. Women’s pages in newspapers were very popular in the first half of the 1900s. This one in 1936 details how a model woman would dress, and so department stores that stocked the latest fashions were making sure women could achieve that, so the advert just meant that women knew exactly where to go to for the looks desired.

With a prominent women’s liberation movement taking wind in the 1960s and 1970s there was a “New Woman” feel to advertisements. An air of a newfound equality behind ads as women were resisting the housewife role and emerging more in workplaces, so advertisements had to reflect this. This came at the same time where local department stores were being bought by much larger chain stores, Plummers & Roddis and Bobby’s were both bought out by Debenhams. This meant that advertising was consumed on a more national level as chain stores advertised wider and people were having similar consumer experiences. A Debenhams advert that came from a magazine in the 1970s shows this idea of the “new woman”, promoting a more liberal fashion. Somewhat fun and colourful with modern fabrics to symbolise the liberation and movement away from the past that modern women were striving for. Nonetheless, these ads were rooted in the idea that women’s clothing choices for work meant wearing fashions that would please male supervisors, as this would be the way for women to succeed in the workplace alongside men. That being so, while women were pushing against stereotypes and fighting for equality, advertisements were keeping up with the illusion of this and the new woman because they needed to sell to women, but they were never too radical to move away from stereotypes and narratives that aided to keep women’s places at home.

One thing to consider is the major decline in department stores and other high street stores since the 1990s. As this has meant that overtime the impact of their advertisements has diminished with them. Instead, other individual brands have taken on a bigger role in advertising. In 2018 it was found that nearly 650 retail and restaurant brands have closed or gone into administration, including House of Fraser and Beales in 2020. Therefore, while gendered and stereotypical advertising can be somewhat originated back to department stores, the advertising industry has increased dramatically, especially with the internet and tailored advertisements according to data.

However, just because advertising has only increased over the decades, progress in combating these harmful stereotypical images has been present. The Dove Campaign for example, Dove have been around since 1957, so very well may have been stocked in these department stores that we have looked at. In their own advertising campaigns, they now promote “real” women in their body types, and diversity in those who use their products, and are most successful on social media platforms. This demonstrates that companies no longer need to conform to gender norms in order to be successful when department stores arguably may have needed this.

So, with the ban in 2019, while it is clear it does not go far enough in directing advertisers to stop using gender stereotypes at all, it is a clear step in the right direction. Next time you see an ad on Facebook that portrays strikingly annoying stereotypes, report it. The open rejection in choosing the content you consume on a day-to-day basis means that advertisers will have no choice but to leave them behind. Women have historically, even in local areas like Bournemouth, been fed ideals that they should meet even with developments in feminism and equality. But the end is in sight.

Further reading:

Kaitlyn Tiffany. “Gender Stereotypes have been banned from British ads. What does that mean?”. Vox. 18 June 2019.

Peter Scott & James Walker. “Advertising, promotion, and the competitive advantage of interwar British department stores”. The economic History Review, vol 63, No 4. (2010) pgs 1105-1128.

Sonia Fillipow. “Advertising and the “New Woman”. Consuming women, liberating women: Women and Advertising in the Mid-20th Century. 2019.

Vicki Crowe. “Is this the end for the British high street?”. Which. 23 June 2018.

Chuxian. “All about #RealBeauty – Dove”. Medium. com. 13 June 2017.https://medium.com/@cx_wang/all-about-real-beauty-dove-fbffee9df21c